The Economics Society of Australia (ESA) has released its latest survey of Australian economists on the question, “Does privatisation of human services hurt outcomes?”

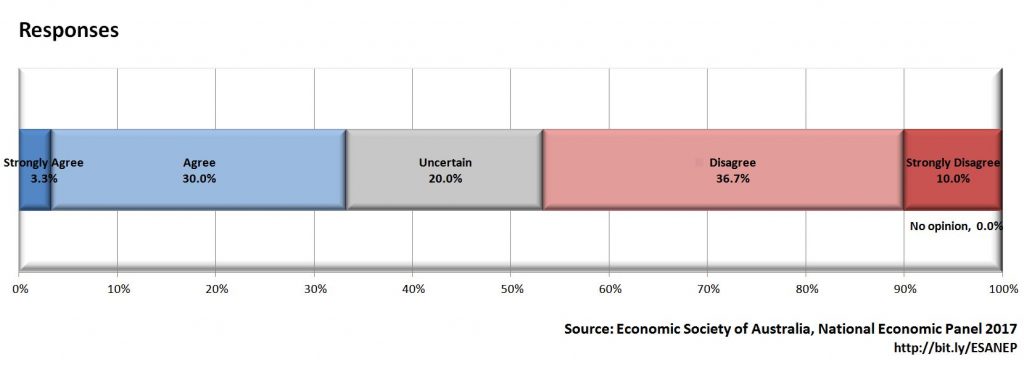

Not surprisingly, the economists don’t agree: 47% of the 54-person panel disagreed or strongly disagreed with the above statement, 20% sat on the fence, and 33% agreed or strongly agreed.

Selections from the commentary by Professor Anthony Scott (University of Melbourne, pictured), below show that:

- VET was singled out as a particular failure of the market approach to government services.

- There was an acknowledgement that as not-for-profit providers are more “altruistic” with “welfare-maximising objectives”, this reduces “the need for strong incentives.”

- It’s easiest to service good students, so private for-profit providers will discriminate without extensive regulation in the education space.

- There was strong support to maintain the status quo of government outsourcing.

Dr Don Perlgut, CEO of Community Colleges Australia, commented on the analysis: “Economists are notoriously conservative and market-driven in their analysis of human service provision. So it is very instructive to see that a large proportion of economists are questioning government outsourcing to for-profit providers.”

“There also seems to be strong agreement that VET should not be included in additional outsourcing, and that the not-for-profit sector has a crucial role to play in delivering government-funded education and health services,” Dr Perlgut said.

*****

Selections of Professor Scott’s analysis are below (italics are included by CCA for emphasis). The full analysis is available here.

“Improving both the level of and access to health care and education are important societal objectives. Equity of access and universal access is perhaps more important than efficiency in the provision of these services. The health and education sectors in Australia are characterised by a relatively large share of both private for-profit and not-for-profit provision and private finance.

“For-profit provision of public services is controversial due to a range of market failures, notably price signals being distorted by insurance and/or government subsidies, and prices, if they exist at all, not reflecting demand due to informational asymmetries between providers and consumers. In these sectors it is also difficult to measure outcomes or quality, particularly in health care where there is no routine measurement of patients’ health improvements after receiving care. There is a high chance that consumers could be disadvantaged in such markets. In both the health and education sectors, these issues have led to regulation of providers in terms of licencing, minimum standards, and regulation of government funding.

“Though most seemed to disagree with the statement, this was because poor outcomes and high costs to government were possible only if there was weak oversight and regulation.

“If one is concerned about access to health care and education, then for-profit provision often results in adverse selection of either the healthiest patients or brightest students, as these are also the least costly. Evidence suggests that better observed client outcomes from for-profit providers is driven by selection rather improved efficiency. Incentives therefore need to be in place to limit selection.

“There are examples where moving from public to for-profit provision has led to poor outcomes and panellists mentioned the opening of the Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector to private provision (John Quiggin, Beth Webster). This depends not only on regulation but on the ethical standards of the professions in these organisations.

“There was also strong support for the status quo in Australia.

“Not-for-profit providers maybe more altruistic and have welfare-maximising objectives (Rana Roy) which reduces the need for strong incentives. But in for-profit provision: “it is often difficult for clients to assess the level of quality prior to purchase and there are incentives for private providers to exploit the system and drive up costs to both governments and clients.” (Lisa Cameron)