CCA's CEO, Dr Don Perlgut, has just published an article on LinkedIn, which is reproduced below:

More than two million Australians may soon be out of work. Unemployment will soar to at least 15%, compared to the recent rate of 5.1%: “scenes reminiscent of the Great Depression.” Lengthy queues at Centrelink offices yesterday in Sydney and Melbourne. The Australian Government “MyGov” website crashes under the weight of thousands trying to access it.

Welcome to Australia, circa late March 2020, as the economic and social impacts of the Coronavirus – our worst public health crisis in more than 100 years – increase and “social distancing” results in the mandated closure of restaurants, bars, pubs, entertainment venues and much more. What was only science fiction a few weeks ago – Australian states and territories closing their borders to each other, as they did in 1919 in response to the Spanish flu – is now a reality: Tasmania, Western Australia, South Australia, the Northern Territory even Queensland have done it.

Some of the worst hit will be owners and employees of small businesses, most of whom cannot weather a shutdown of three months, let alone the six months or more, as money is “instantly sucked out of small and medium-sized businesses that rely on face-to-face trade.”

Disadvantaged Australians and the current crisis

Events are moving so fast with the Coronavirus impacts that it is impossible to keep the full picture of what is happening in your head. One thing is clear: the poor are “the biggest losers in every recession and that will be just as true in the ‘coronacession.’ Those who are able to keep working will be the least affected; those who lose their jobs will be the most affected” (Ross Gittins, Sydney Morning Herald 23 March 2020).

“Equality and inclusion are not afterthoughts during a public health crisis. That is especially the case during times like these: inequality becomes even more dire and dangerous when people on the margins of society are the most at-risk,” writes Liam Getreu.

Prior to the onset of the current crisis, despite its strong economy Australia already had persistent economic inequality, with the wealthiest 20% of Australians owning nearly two thirds of all wealth, while the lowest half own just 18%, and the lowest 20% having virtually no wealth at all.

Australia’s most vulnerable and disadvantaged groups are also those which disproportionately served in much greater percentages in education and training by Australia’s not-for-profit community education providers, easily outstripping TAFE and private for-profit providers: see CCA’s September 2019 research report (PDF).

The groups well-served by community providers include:

- Australians in the bottom two “SEIFA” quintiles – those in the lowest 40% of socio-economic advantage;

- Indigenous Australians, who are especially vulnerable to the Coronavirus through higher rates of chronic disease and rates of poverty that result in over-crowded housing;

- residents of regional, rural and remote Australia – many of whom have not yet recovered from devastating drought and unprecedented bushfires – and who are especially vulnerable because of limited medical services, thin “supply chains” of essential goods and higher unemployment rates to start with;

- residents of outer metropolitan areas, who experience some of the same inequalities of transport and accessibility as regional areas do (see CCA’s research report on Western Sydney);

- people with disabilities, who already experience workforce, social and health challenges, and are finding some of their essential support services cut;

- older workers (age 45+) and elderly Australians, many of whom – especially with underlying chronic diseases – are already among the most vulnerable to unemployment, with 50% higher unemployment rates even prior to the crisis commencement – and we know that older (age 60+) Australians will be the most vulnerable to the most severe effects of the virus; and

- refugees and older migrants, many of them concentrated in particular locations in Sydney and Melbourne, experiencing major challenges in learning English and assimilating into Australian social, economic and cultural life.

The Australian vulnerable and disadvantaged population is about to increase exponentially

Parts of the Australian and international economy are in meltdown, with transportation, hospitality and entertainment sectors among the first impacted. Three of four working adults in a middle-class family I know in suburban Sydney are about to lose their jobs: this economic and social impact is profound and has begun to reach deep into middle Australia, including those never previously deemed vulnerable or at risk.

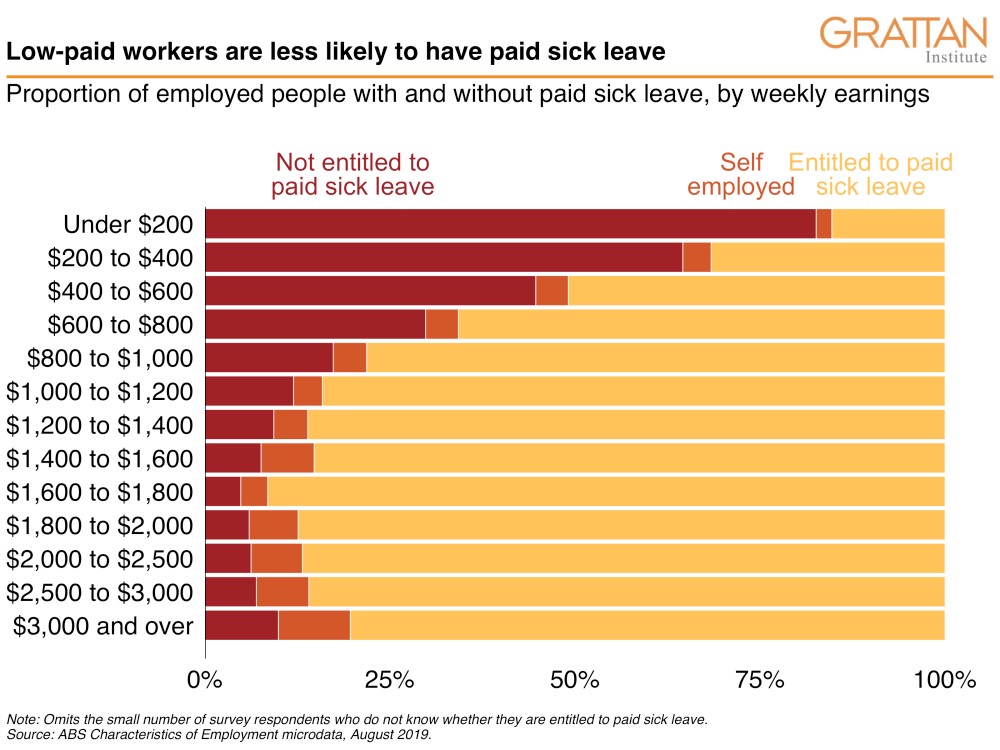

Figures just released by the Grattan Institute show that 37% of Australian workers do not have paid leave entitlements, and are therefore especially vulnerable financially if they lose their jobs or get sick. The situation is particularly acute for low income workers, very few of whom have leave entitlements (see graph below). “Of 12.5 million Australian workers, about 2.4 million of them are casual employees – with no paid sick or annual leave, and no entitlement to ongoing work – and a further 2.2 million are self-employed.”

“Of 12.5 million Australian workers, about 2.4 million of them are casual employees – with no paid sick or annual leave, and no entitlement to ongoing work – and a further 2.2 million are self-employed.”

Although “young people are disproportionately likely to be in casual work and not have paid leave,” it’s not just the young. “More than a quarter of people in their 30s, 40s, and 50s do not have paid sick leave, either because they’re casual workers or they’re self-employed,” including about 1.5 million, a third of all working parents, says the Grattan report. Many of these 4.6 million Australian workers were among those who queued in front of Centrelink offices yesterday and today.

Australia is facing a crisis of increasing unemployment and under-employment not seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Fortunately, Commonwealth Government intervention is coming quickly and income support is increasing in a manner few could have believed possible only a few short weeks ago. But the fact remains: our vulnerable population just got a whole lot bigger, and we are only in the early stages of the Coronavirus crisis. What will the situation be in three, six or nine months’ time? No-one knows, and only few would hazard a guess.

The role of Australia’s social sector and community education providers

The Commonwealth Government is the income support provider for Australians, and the states and territories deliver extensive social services. Yet a large proportion of social and community services are now delivered by not-for-profit organisations and charities, which employ more than 1.3 million staff, rely on the contributions of over 3.5 million volunteers, and contribute 8% of Australia’s GDP.

Australia’s social sector has a major role to play in both mitigating the developing social, economic and health impacts of the Coronavirus as it proceeds, and in providing institutional and social infrastructure support to Australians once the crisis has passed. So maintenance of the social sector’s capacity through this crisis is essential.

A crucial part of Australia’s not-for-profit (or “for purpose”) sector are the 400+ adult and community education (ACE) organisations, which serve almost 12% of accredited vocational education and training (VET) students, with a special focus on the most vulnerable and disadvantaged learners and foundation skills of language, literacy and numeracy. These community education providers are over-represented in regional and rural communities, and excel at engaging small businesses, which have been particularly hard hit by the Coronavirus impacts.

Aside from place-based education and training, these organisations often provide the “glue” keeps their communities functioning, ensuring the maintenance of community social capital and a properly functioning Australian democracy.

Like many small and medium-size businesses, the community education sector has been badly affected by the Coronavirus slowdown, with few students still attending in-person classes. The sector has shown its flexibility and adaptability, with many starting to plan for digital and online learning and other innovative ways of engaging their students. Encouraging and supporting these community training activities are two of the most important areas for governments.

The Coronavirus is a once-in-several-generations event. It is incumbent on us to look to the end of the crisis, and to envision which institutions need to survive, ones that will assist the inevitable social and economic re-building that will occur. Australian adult and community education organisations need to sit high on that list.